Yet meet him in his cabin rude,

from Tipperary by Thomas Davis

Or dancing with his dark-haired Mary,

You’d swear they knew no other mood

But Mirth and Love in Tipperary!

I was flicking through an agricultural reference book published in Ireland in the 1950’s: I was trying to get details on soil types (which was mind numbing) so I was only delighted to spot what was inside the front cover: the author had included the verse above, it’s fourth stanza of the Thomas Davis’ poem Tipperary. I’ve an awful weakness for bits of verse, they be teasing me into digging out the full poem and finding out more. I duly took the bait. What I wasn’t expecting was that Davis’ writing (from over 170 years ago) would resonate with today’s immigration debate, which is one of the main campaign issues in this years Irish General Election Campaign. As I write voting is just over a week away.

Immigration has become a really toxic issue in Ireland in recent years. Prior to the early 2000’s we didn’t have much immigration because to be blunt we were poor and no one wanted to come here. For centuries our greatest export was people. This wasn’t just in the immediate years after the potato famine. Unfortunately not. Around two thirds of the people born after World War 1 and the end of World War 2 emigrated. Two thirds! By way of another example the population of my border county Monaghan kept falling from the late 1840’s right up until the 1970’s. The population declined here for over 120 years.

In the 1990’s we had 15 to 20% unemployment and young people were escaping this sinking ship for brighter opportunities elsewhere. I remember around then myself and my father got lost near Letterfrack in County Mayo. We stopped and asked a young fella at a gate feeding sheep where the road would bring us. He gave us this sad look and said, “every road round here leads to the airport”. No joke! There was just a gloom and hopelessness in the air right up into the mid 1990’s. (He did give us proper directions in the end.) But as the hopelessness and emigration stopped the tide started to turn the other way, especially from the 2000’s onwards.

So while immigration is a relatively new phenomena in Ireland it’s worth remembering that bitter disagreement around integration and different types of people aren’t new on this island. We’ve been grappling with invasion, colonisation, religious intolerance and mixed political allegiance for centuries. During this time there’s been lot’s of extreme rhetoric about how Irish society could or should look. So the rhetoric of the contemporary era isn’t new. And in fact it’s good to hear from some of the thinkers of the past. Which is where the broader writings of Davis are enlightening.

Back to Tipperary, by Thomas Davis: it has eight stanzas which detail the many virtues of the ordinary people of Tipperary while lashing the evils of the nasty British overlords. This type of poetry was popular reading in 1800’s Ireland and a stark contrast to the anti-Irish diatribes that filled the pro British newspapers at the time. In this particular poem, Thomas Davis writes about how few could face the mighty men of Tipperary in battle. Davis then goes on to praise the homeliness of these same fearsome warriors.

Davis, born in 1814, was a journalist for The Nation newspaper (which was a nationalist, pro independence publication) and also a Young Irelander. The Young Irelanders were political and cultural champions in the 1840s committed to an all-Ireland struggle for independence and democratic reform. Davis and his buddies in the Young Irelanders were part of an educated middle class who saw the injustice in Irish society around them. What I find great about this is that Davis himself was a Protestant, his father was Welsh and served in the Royal Artillery. But who your father was or what your Mother’s religion happened to be wasn’t a problem for the Young Irelanders. They wanted ordinary people, regardless of their differences, to have basic rights and a say in how Ireland was Governed. This was an era when most Irish people were peasant farmers paying high rents, often to privileged, wealthy Landlords. Political power lay with the monied elites and the land owning ascendancy who were loyal to the English Crown and who tried to maintain the status quo.

Davis was quoted as saying that Young Irelanders should “teach the people to sing the songs of their country that they may keep alive in their minds the love of the fatherland.” (Davis uses the word fatherland which is interesting because Ireland is more often portrayed in literature and prose as a female figure but thats for another day.) So Davis felt the Irish needed songs to sing and he composed the popular Rebel song “A Nation Once Again” and the widely covered “The Wests Asleep”. The later song, The Wests Asleep is about how the fighting spirit of Ireland needed revival from slumber and how, poof! Up the fighting spirit could pop at the darkest hour.

Reading the lyrics rarely does a song much justice and as regards the Wests Asleep, few bands give Davis’ song the same oomph as folk legends the Clancy Brothers and Tommy Makem. At this point I could tell ye all about how the Clancy’s were Tipperary men, tie the whole things back to Tipp’, the subject of Thomas Davis’ poem, but instead lets pay a quick homage to the Irish cultural icon that is the Aran Jumper.

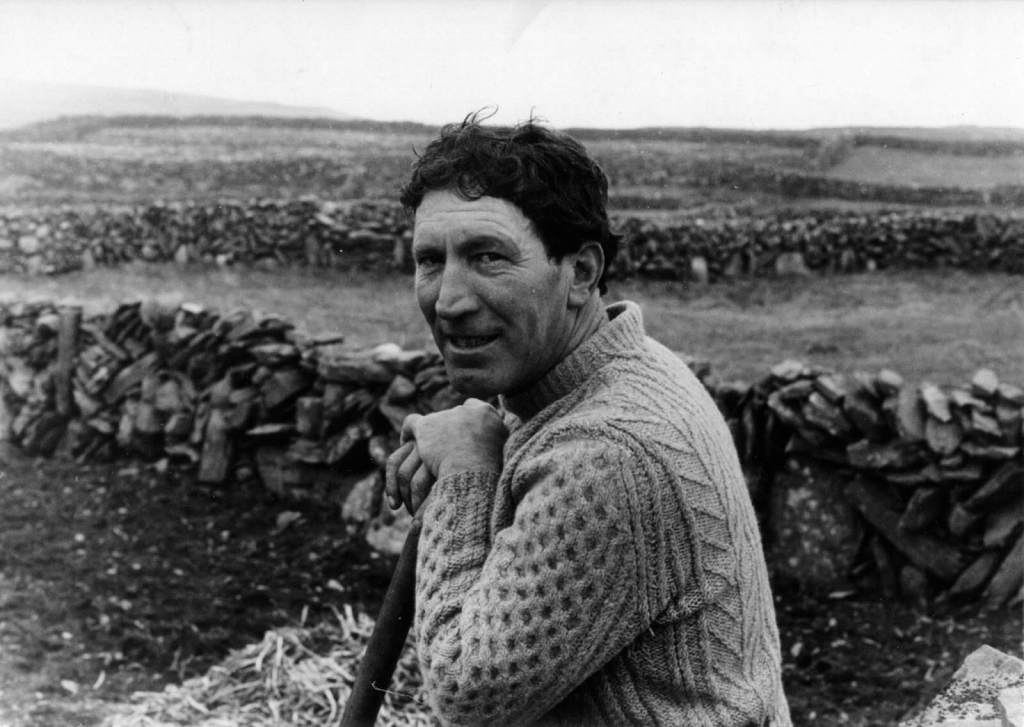

The Aran Jumper is a typically an off-white knitted woollen jumper with Celtic patterns running through it. And the Clancy Brothers and Makem were the most famous Irish folk group ever to pull their heads through the neck of these illustrious jumpers. And when I say pull your head through the neck of an Aran Jumper I mean ye should be nearly sweating trying to yank your head through and up into a good Aran Jumper. From the 1940’s onwards the Aran Jumper was marketed abroad as the jumper of choice for a race of people born with the Atlantic wind whistling through their salty hair – no talk of dandruff back then. The impression was that wearers of Aran Jumper spent their days battling the elements and their evenings smoking pipes by open fires, wind whistling down the chimney above their heads. Irish ex-pats loved that image and sales of Aran Jumpers abroad boomed.

I remember an auld fella on an island out off the coast of Galway arguing that you weren’t really Irish unless you had at least one Aran Jumper in your wardrobe. A pair of wooly socks or a woolly beanie hat wasn’t enough. His view was that Scots have kilts and more power to them. But we have Aran Jumper. Ye might never wear the itchy thing but that’s not the point cause ye’d never know when the English might come back and steal your home heating oil. So have a few pure wool Aran Jumpers as an insurance policy. I don’t know if the talk about intergeneration trauma from English occupation is actually true, but either way, I took his advice. One thing is certain: Aran Jumpers were no bad thing for the people of the Galway islands and other communities along the Atlantic coast – production of the famous geansaí (Irish for jumper) was a crucial cottage industry providing much needed employment for struggling families from the 1900’s onwards.

So as I mentioned, the Clancy Brothers and Makem (see the still image below) were fine lads to wear the Aran Jumper. They were also great hearty lads for singing old rebel songs, and auld come-all-ye’s. This link brings you straight to the last verse where they bring Tomas Davis’ song The Wests Awake, from a whimper to a roar. I’ve also included the lyrics themselves below for those who might struggle with the accents.

And if, when all a vigil keep,

Extract from The Wests Asleep by Thomas Davis

The West’s asleep, the West’s asleep—

Alas! and well may Erin weep,

That Connaught lies in slumber deep.

But, hark! some voice like thunder spake:

“The West’s awake! the West’s awake!”—

“Sing oh! hurra! let England quake,

We’ll watch till death for Erin’s sake!”

But despite the tub thumping rebel songs that Thomas Davis and others composed there were relatively few Tipperary men taking time out of the grind and hardship of subsistence farming to rise up in battle. That’s revealing in itself: we had a few badly planned and executed rebellions over several hundred years which often achieved very little. It’s astounding how in Ireland, as in India and other former colonies, a foreign power was able to maintain control over millions of subjects for centuries. It’s something to do with the psyche of a poor, colonised people – lacking confidence, lacking belief in their own leaders, lacking faith in their own ability to rise up for equality and to demand improvements. And so when blight repeatedly decimated the potato crop in the 1840’s the Irish starved to rather than rise up in rebellion. And all this starvation happened while huge quantities of other foods grown in Ireland were exported.

Nowadays you’ll more often hear the “Great Hunger” (an Gorta Mór in Irish) used (rather than the Irish Famine) to refer to that period in Irish history because there was never a complete shortage of food. Much of the excess was simply exported to earn higher prices abroad. And since I mention the Great Hunger I can’t go past the Monaghan poet Patrick Kavanagh who wrote a poem called the Great Hunger. It explores the harsh realities of life in the Irish countryside.

O the grip, O the grip of irregular fields! No man escapes.

It could not be that back of the hills love was free

And ditches straight.

No monster hand lifted up children and put down apes

As here.

Nowadays Kavanagh is a national hero but was despised by many in his own era, especially where he grew up. That’s cause ye couldn’t go writing that your neighbours were effectively apes and not face backlash in the Ireland of 1942. At that time in the 1940’s the Irish Government was deeply conservative, both religiously and culturally and they pushed a nationalistic agenda – they tried to distract the population from the States many failures by brainwashing us into believing that we were and always had been, culturally pure and unique. So despite the wealth and prosperity that’s evident around us there’s still this social conservatism and suspicion among some in Ireland, especially around immigrants coming in. Some Irish people question whether there’ll be enough for everyone who’s already here – others take this further and are openly racist – you can see plenty of this toxicity on social media. All this is a roundabout way to describe the historical path and the ideas that shaped the Ireland of today.

And what about Davis? The man who wrote about Mirth and Love in Tipperary and the West Awake, also left us these words where he advocated an inclusive nationality…

“. . . which may embrace Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter – Milesian and Cromwellian – the Irishman of a hundred generations, and the stranger who is within our gates.”

Pretty far sighted stuff and given the heated rhetoric that surrounds modern immigration, something we could do with remembering.

And that’s all from this ape until next time.